Who can deny the power music lends to a motion picture? I do realize there are some great movies that do not have musical scores (please refer to the following website for more information https://screencrush.com/films-with-no-soundtrack-list/, but they are the exception, and not the rule. Imagine watching one of your favorite movies with the music soundtrack removed. Do you think your movie-watching experience would be different?

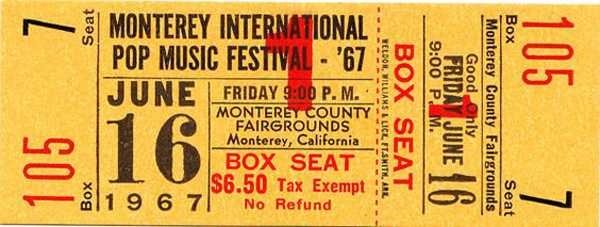

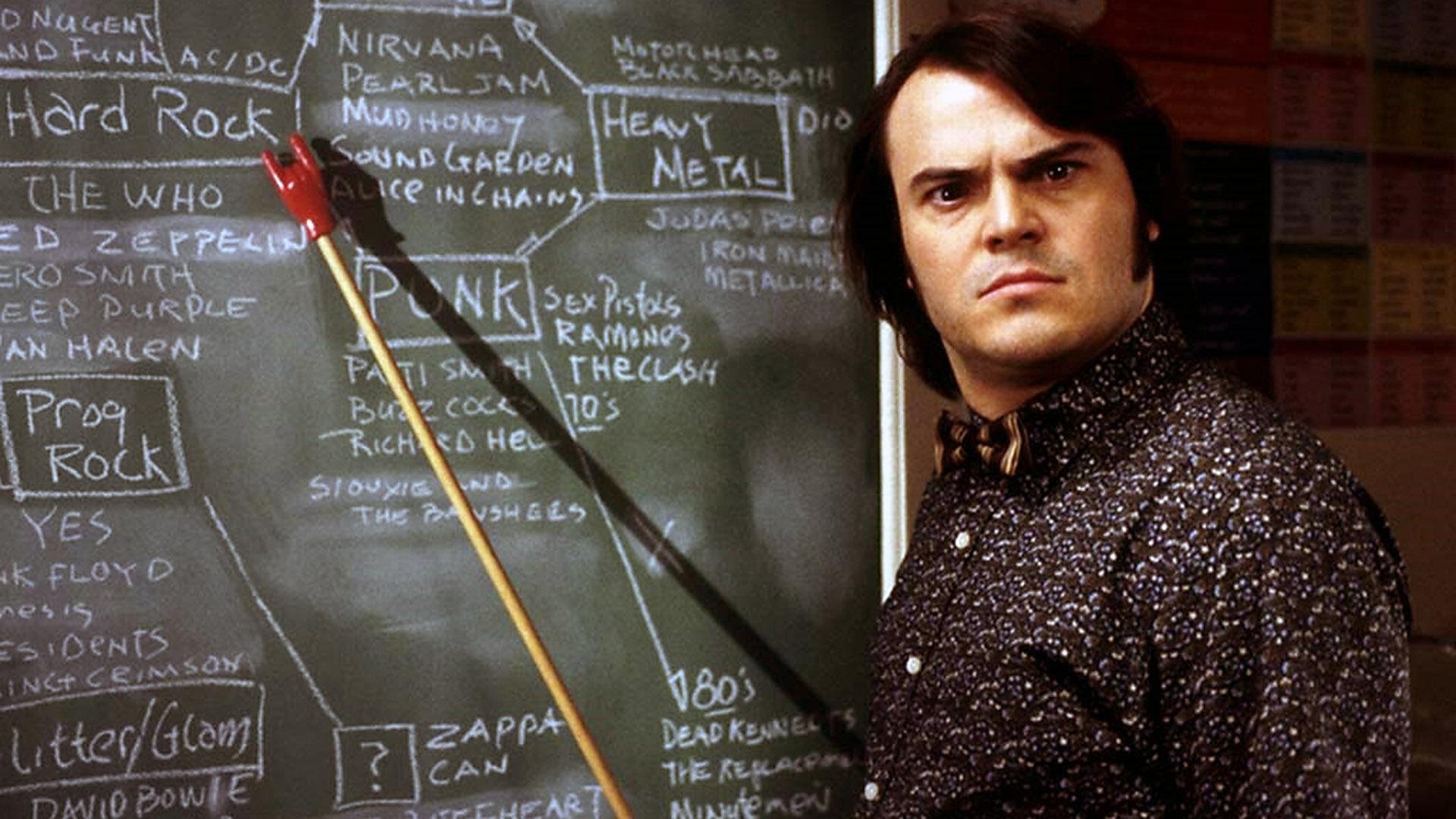

Some of my favorite movie soundtracks include The Godfather, The Graduate, Help, A Hard Day’s Night, Gladiator, Pretty in Pink, and Pulp Fiction. I am also a huge fan of movies where music is central to the theme, including (a) rock operas (Quadrophenia, Tommy, and The Wall); (b) concert films and rock documentaries (Gimme Shelter, The Kids Are Alright, and Woodstock); and (c) motion pictures that revolve around the lives of famous musicians (Bird and Miles Ahead). I recently watched Born to be Blue, which starred Ethan Hawke as famed jazz trumpeter Chet Baker. The movie centered on Chet Baker’s controversial, and often painful, musical comeback in the late 1960s. While this is just my opinion, I thought Ethan Hawke gave a wonderfully convincing performance. In addition, I thought the soundtrack was excellent. I also enjoy unique soundtracks. For example, the main theme for The Taking of Pelham 123 combined a funk rhythm line with a 12-tone row melody. Check out the link below. The music works!

Academically speaking, what does the previous research have to say about film music? Tannenbaum (1956) conducted a study in which participants responded to semantic differential scales while watching several versions of a drama (i.e., staged drama, televised drama, and filmed version of the staged drama). Results indicated that background music in the production increased participants’ responses according to the bipolar adjectives of fast/slow and strong/weak. While an early study, Tannebaum was able to describe the influence music can have in entertainment.

More recently, it has been found that music depicting an exciting situation on film can heighten feelings of anger, while music depicting a sentimental situation can heighten feelings of love. Such examples show that music can help an audience to better understand, and heighten empathy, towards the characters in a film.

Today, researchers in the field of neuroscience are conducting studies to determine how a person’s brain processes audio and visual information while watching a film. The results of such research have numerous implications for the film and video game industries (not to mention the use of music in corporate advertising).

There is no denying that music provides a valuable contribution to the world of film, and while previous research in this area is rather sparse, current and future research may prove to be quite intriguing. For those of you who are interested in exploring this topic further, I encourage you to read The Psychology of Music in Multimedia by Tan, Chen, Lipscomb, and Kendall (2013).

If you have the inclination, please feel free to share your favorite movie soundtracks! I’m sure we can create quite a list. For your weekly assignment, please do the following:

- All of the readings are available on the course D2L site. This week, your topic choices are:

- Film Music

- File Sharing

- Manipulation

This week, I chose to write about film music, but you can address any of the above topics. The readings are short and interesting. I encourage you to read as many as possible.

- Choose one of the topics and post a thread (500 words minimum) by 11:59 p.m. on Friday, April 14th. Do not attempt to summarize the entire article. Instead, try to expand on a particular topic (or topics) within the chapter that is/are of interest to you.

- By 11:59 p.m. on Sunday, April 16th, please post a response (200 word minimum) to TWO threads created by your classmates.

Tan, S. L., Cohen, A. J., Lipscomb, S. D., & Kendall R. A., (2013). The psychology of music in multimedia. Oxford Scholarship Online.

Tannenbaum, P. H. (1956). Music background in the judgment of stage and television drama. Audiovisual Communication Review. 4(92). doi:10.1007/BF02717069

Thompson, W. F. (Ed.). (2014). Music in the social and behavioral sciences: An encyclopedia (Vols. 1-2). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.